This page describes a chess variant I'll call Fresh Chess. It's intended to address what I see as the biggest problems in chess: the frequency of draws, and the importance of preparation: memorizing openings. I'm not the first to identify these as problems, nor to propose changing the rules to solve them.

The problem with draws is not that they're boring: many are, but some aren't. The problem is that the relative ease of drawing, as opposed to winning, enables players to "play for a draw", for instance if they're up a game in a match. If draws didn't count as games, as used to be the case, then they'd simply be failed attempts to arrive at a decisive result. But now they change the character of the sport entirely, and not for the better.

Why is it a problem that preparation is so important? Well, it isn't ... if you like preparation, or watching prepared openings. But many people feel the game "really starts" when players exhaust their preparation and have to think on their own. For them, the earlier in a game that occurs, the better.

Many people also enjoy the midgame more than the endgame, both as a player and as a spectator. They feel we see too many games in which one player gets a small advantage, say he doubles his opponent's pawn, and then trades down to get an endgame where he may be able to grind out a very technical victory, and if not, it's just a draw. We can admire someone who does that well, but still regret not seeing a different style of play.

The changes I'm proposing are intended to encourage more midgame and less opening and endgame. If that's not what you like, then you won't like them!

Draws currently represent about 55% of all tournament games. Until 1867, they were simply replayed: they didn't count as games. Now the two players share half a victory equally. This makes it much easier for tournament organizers, but penalizes the spectators.

These rules won't eliminate draws entirely, but they will go a long way towards that goal. The draws that still arise will be decisive, like Armageddon: the game ends without a checkmate, but with a winner.

A draw may arise in several different ways:

We'll consider them all.

Few players know that stalemate was not always considered a draw. The goal of a chess game is not checkmate; it is to kill the enemy king - checkmate is simply the mandatory precursor. Stalemate is the equivalent of capturing the king without killing him, and should also be a victory.

But we can introduce a more subtle fix: allow players to "pass" - to choose not to move. After all, on a field of battle, you are not obligated to act if that doesn't seem in your best interests - why should you be in chess? Thus, in a stalemate, the losing player must pass - it's his only legal move - and the winning player must continue to the win by delivering check. This rule would also prevent Zugzwang, and some meaningless moves where one player is simply waiting for the other to attack. If the other player also passes, the first cannot pass again - see below.

Threefold repetition arises simply because the players have no better move. OK, so let's oblige them to make a different move! You tried Plan A, your opponent responded well, now try something else! Here's the rule: You aren't allowed to make a move that would return the board to a position that it's already been in this game. Threefold repetition and perpetual check thus become simply impossible, as does passing a third time in a row.Although it is theoretically possible to return to a previous position after a long sequence of intervening moves, in practice, it is usually enough to remember the last few moves. Every time a piece is captured or a pawn is advanced, a repetition becomes (almost) impossible.

The fifty-move rule and the insufficient material rule derive from the same problem: Neither player can win with the material remaining on the board. Put that way, the solution is obvious: add more material! The details are less obvious, but here's a proposal.At any moment in the game, as his turn, instead of offering a draw, either player may call for reinforcements. He specifies the value (see below) of the reinforcing force that he is willing to accept in exchange for conceding victory to the other player in case of a draw, like in Armageddon.

His opponent then responds with an offer to accept a weaker reinforcing force, and the two of them alternate bidding less and less until one will not accept any lower value. The bid values can go all the way to zero or even beyond: a bid of -1 means that you give your opponent another pawn and still believe he can't even earn a draw.

If instead of bidding a lower value, you bid the same value as your opponent just did, then he gets a chance to bid even lower. If he refuses, then both players get the bid value in reinforcements, with neither winning in a draw. But as you play on, there might arise a shift in advantage enough to unbalance future bidding.

During the bidding process, each player makes his bid instead of moving, and then punches the clock, allowing the other player to bid. Once the bidding is over, if the player accepting the other's bid is next to move, he then moves and punches the clock; if not, he simply punches the clock to signal his acceptance, and the game continues.

Over the course of the rest of the game, the player who won the bidding war - who has accepted to lose in a draw in exchange for getting "reinforcements" - may then spend his value, using the piece values below, to bring lost pieces back into the game, one at a time, as a move, by placing them where he likes on his first rank. He's not obligated to place a reinforcement if he'd rather move an existing piece. The pieces don't have to have been lost before the bidding.

Agreeing to a draw can simply be banned: make players play it out. Of course they agree to a draw because they foresee a draw by one of the other avenues, but maybe we don't see it. Or maybe they're short on time, and if forced to continue, they might simply flag out or blunder. Let's see!Another problem involves the depth of preparation. In chess, studying opening theory is a huge advantage, and it's not clear how that benefits the spectators. It's to address this problem that Fischerrandom (Chess 960) was invented.

But why not go further? Let each player choose his own opening positions! After all, that's what generals do before a battle: they choose the disposition of their forces.

So before a game of Fresh Chess, each player would secretly record the opening positions of his pieces in the first rank (just write down the one-letter abbreviations from file A to file H, e.g. RNBQKBNR). He can place them anywhere, even with both bishops on the same color (as in Shuffle Chess). But there's one limitation: the King must start on the Kingside (e1-h1). This prevents games from being won or lost before the first move based on whether you guessed correctly which side the King would be on. The second rank is always a row of pawns.

As a side benefit, we eliminate castling. If you want your king in the corner, start him there! Perhaps you know that Vladimir Kramnik has made the same suggestion.

Why do pawns get to move two spaces on their first move? It isn't clear why this rule was added in the 15th century; probably to get the action started a little quicker. But since chess began to be studied, the idea of hurtling heedlessly into combat has become unpopular - openings are more circumspect, more about threat than action. So a little more maneuvering before engaging is not going to be a problem. That's especially true since you can choose your opening position and thus get a jump on development. As a side benefit, we eliminate the need for capturing en passant.

Or here's a variant: whenever a pawn moves ahead adjacent to an enemy pawn - advances - the enemy pawn can respond by capturing it en passant, but only on the turn after the advance. That can take place anywhere on the board. For example, if you play 1. e4 ... d5 (the Scandinavian), 2. e5 ... black can respond by taking en passant: his pawn ends up on e4.

Right now, when a pawn is promoted, you can choose any piece except a king. But in Fresh Chess, you can only choose from among the pieces you've already lost, so for example, you can never have a second queen or a third rook: the queen is the Queen, as long as she's alive. Not only does this mean you'll never need spare pieces, but it also adds an element of strategy: you may want to exchange queens before promoting to get a new queen.

I'm not a big fan of shorter time formats, nor any other means of handicapping the players. I don't want to to make them play while standing on one foot, or while sharing a cage with a hungry tiger. I just want to see good chess ... and I don't watch it live, anyway, so I don't mind if it takes them hours to create a beautiful game. I don't want to look at paintings that have been created in five minutes, either.

In a classical game, the players may have 90 or 120 minutes for the first 40 moves, followed by 30 minutes for the rest of the game, with an addition of 30 seconds per move starting from move one. Because of this rule, players who are running low on time may make silly moves in order to reach time control, when they'll have more time. Why would we want that?

Better would be to have a single increment, for example 3 minutes per move. Each player starts with 3 minutes on the clock, and gets another 3 minutes every time he hits his button on the clock. His time accumulates, so if he only needs 1 minute for his first ten moves, he'll have 29 minutes on his clock after that. There's no longer any motive for silly moves.

Other time formats would have smaller increments: a blitz game may offer only 10 seconds per move. In fact, one interesting idea would be to have the increment decrease over the course of the game. For example, you could start with 3 minutes added per move, but add 2 seconds less each time, so the increment would be only 2 minutes after move 30, 1 minute after move 60, etc. The result is similar to the current fashion for playing a rapid or blitz game after a draw.

I also prefer clock move: you can change your mind about a move until you press the clock. First of all, there are times when a player has an idea, starts to execute it, and then realizes it's a mistake and ends up moving the original piece to a third square. Why would we want that? I want to see the best moves, not the best move with the piece he already touched. Second, clock move gives players an extra quarter-second to keep thinking. It's his time - let him use it as he wants.

Another idea would be to permit the players to agree to add more time, instead of agreeing to a draw. it's a shame when an interesting game is drawn because both players are low on time ... because the game is so interesting, they have to think a lot. When the time format encourages draws, it's a problem.

Here's a variant worth thinking about. Instead of giving players a limited amount of time, let's just measure how much time they use, with no limit. BUT if the game ends in a draw, the player who took less time is credited with the win. So if you're a slow thinker, you need to win :)

In a real war, not all victories are equal. A victory that costs you too much material, or that takes too long, may be Pyrrhic - you win the battle but lose the war. In chess as well, we agree that not all victories are equal. Some are simply boring, or very technical, while others are brilliancies. Most people agree that winning in fewer moves and with more pieces still on the board enhances the victory.

So a radical idea would be to award a variable value for a win based on those criteria. It's easy to measure how many moves were needed. To measure the remaining material, we use a standard metric (with one tweak):

We don't care whether your queen is the original queen, a promoted pawn, or a reinforcement (see above): a queen is a queen. However, the actual formula used to evaluate games, for both winner and loser, is variable, and is announced as part of the match or tournament, just like the time format is now. In rapid or blitz, the formula could also take into account the time left on a player's clock.

As an example, one formula would start with the victory prize of 200 cents (that is: 2.00 points), then add the total value of the pieces that both players have left, and subtract the number of moves you made. If you lost 4 pawns and one of each piece (queen, rook, bishop and knight), you still have 15 cents of material. Let's say your opponent still has 10 cents of material. If you checkmated the enemy king on move 35, your victory is worth 200 + 15 + 10 - 35 = 195 cents.

The loser also gets his game evaluated (if not, he would just sacrifice pieces to reduce the value of his opponent's win), with a different formula: he gets the value of hall the remaining pieces, and the number of moves he lasted. So if he still has a rook, a bishop and 3 pawns, you have 15 cents of material, and he was checkmated on move 50, then his loss is worth 76 cents - better than 0!

Here are the changed rules:

The various different notations for chess moves and positions rely on a conventional encoding of the squares on a chess board: a letter a-h for the file, and a number 1-8 for the rank. This is very parsimonious in ink, but not so much in speech. It's also subject to mishearing - the letters b c d e g all rhyme - and it's not international: the letters and numbers have different names in different languages.

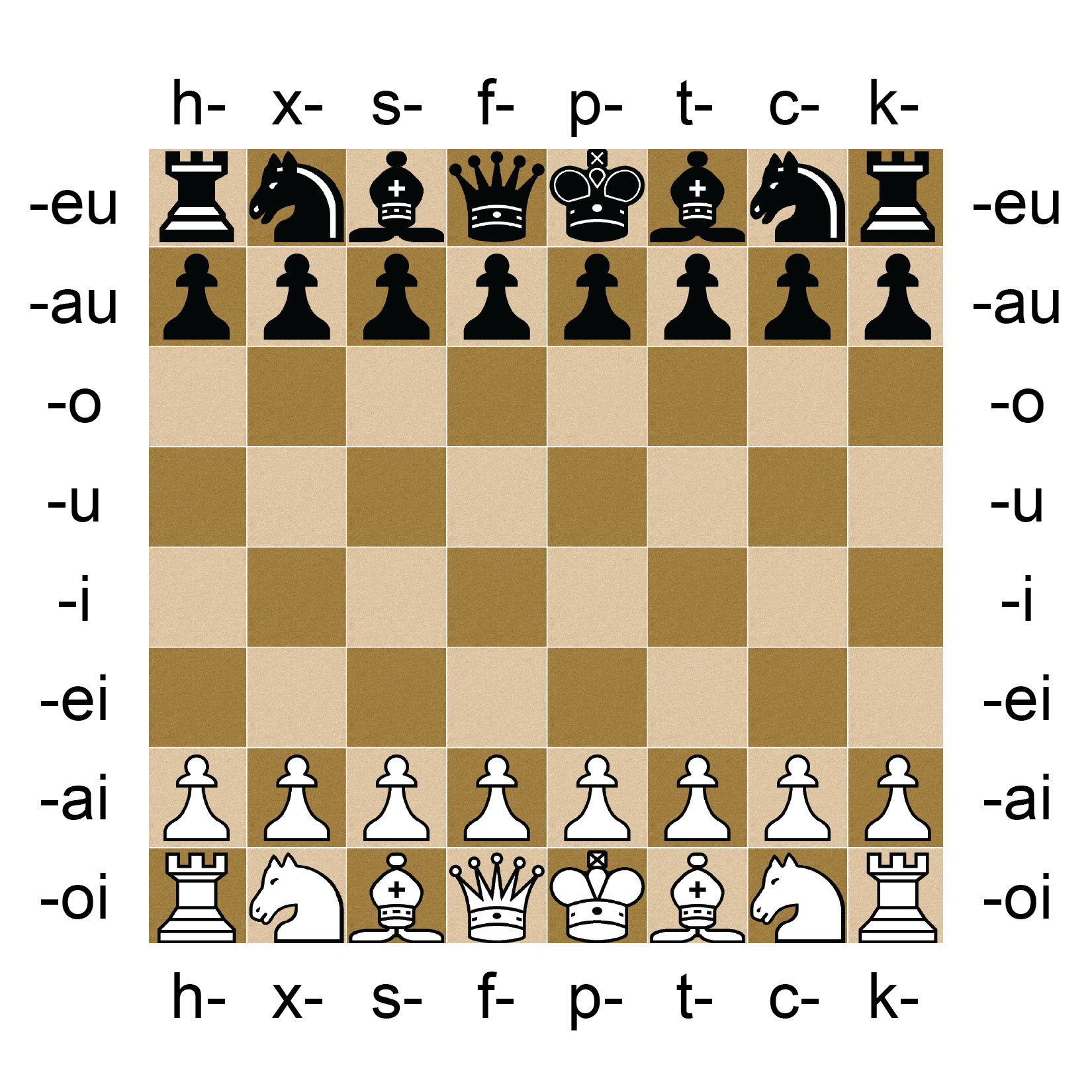

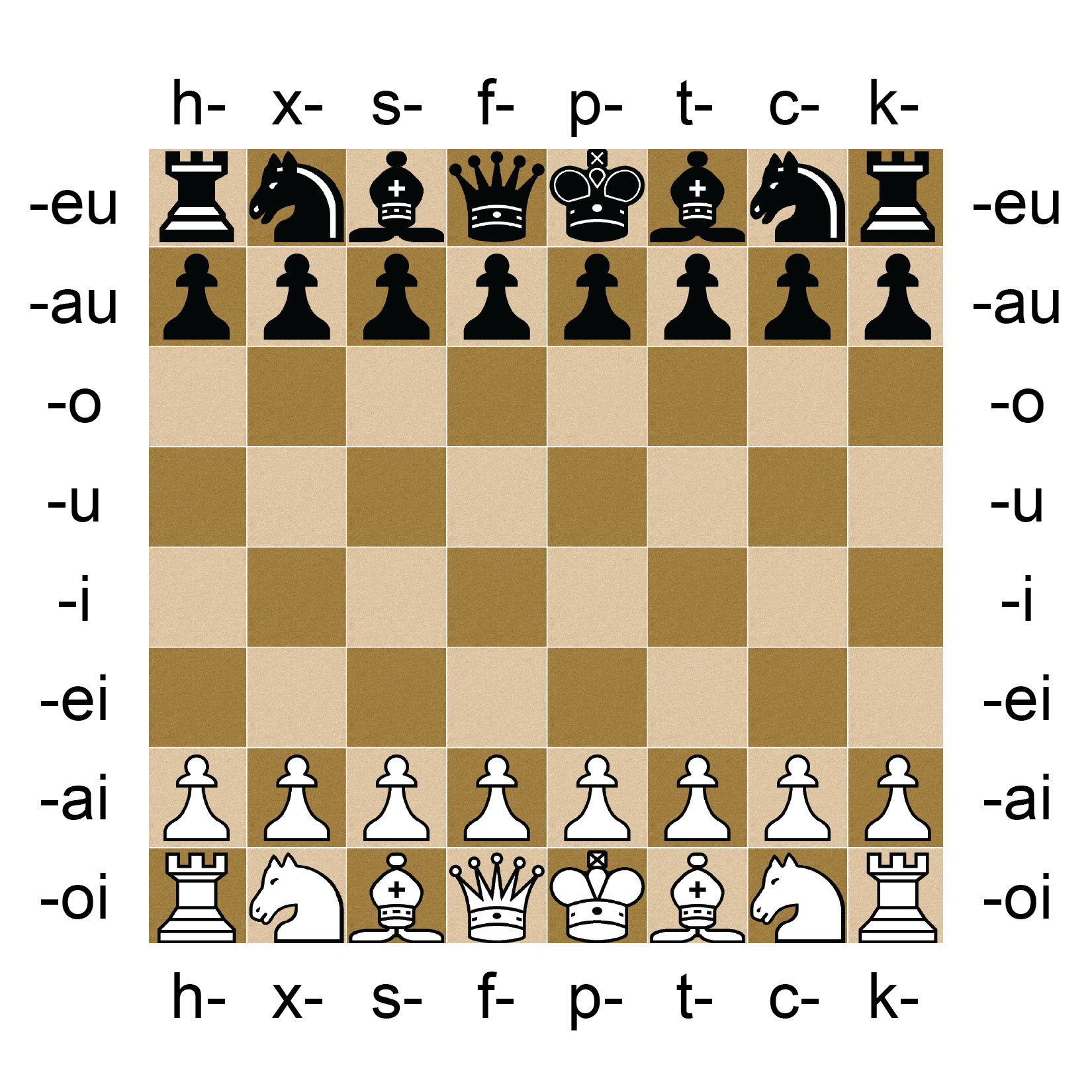

So here we introduce a new notation, in which each square is encoded as a simple syllable: a consonant for the file followed by a vowel or diphthong for the rank. The consonants are (in order) h x s f p t c k, and the vowels/diphthongs (with English examples) are oi ai ei i u o au eu:

Each square is then simply named by the syllable combining the consonant with the diphthong. For example, the starting square for the white king is poi. Here is a labeled board:

The spellings are a little odd for English because they are designed to be read in any Roman-alphabet language. The x is pronounced like sh as in shop, and the c is pronounced like ch as in chop. Some people may pronounce the h with a rasp (e.g. Spanish José) or as a hiatus (e.g. French hibou). The eu diphthong is normally pronounced as written, but in English we pronounce it as the yu sound that distinguishes cue from coo.

To describe a move using this notation, write the position that the piece is moving from, followed by the position that the piece is moving to. So for example, an opening move of e4 becomes paipi.

| © 2002-2026 Alivox | www@alivox.net | 27jan26 |